A newly unsealed FBI document about the investigation at Mar-a-Lago not only offers new details about the probe but also reveals clues about the arguments former President Donald Trump’s legal team intends to make.

A May 25 letter from one of his lawyers, attached as an exhibit to the search affidavit, advances a broad view of presidential power, asserting that the commander-in-chief has absolute authority to declassify whatever he wants — and also that the “primary” law governing the handling of U.S. classified information simply doesn’t apply to the president himself.

The arguments weren’t persuasive enough to the Justice Department to prevent an FBI search of Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate this month, and the affidavit in any event makes clear that investigators are focused on more recent activity — long after Trump left the White House and lost the legal authorities that came with it. Even so, the letter suggests that a defense strategy anchored around presidential powers, a strategy employed during special counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation when Trump actually was president, may again be in play as the probe proceeds.

It’s perhaps not surprising that Trump’s legal team might look for ways to distinguish a former president from other citizens given the penalties imposed over the years for mishandling handling government secrets, including a nine-year prison sentence issued to a former National Security Agency contractor who stored two decades’ worth of classified documents at his Maryland home.

But many legal experts are dubious that claims of such presidential power will hold weight.

“When someone is no longer president, they’re no longer president. That’s the reality of the matter,” said Oona Hathaway, a Yale Law School professor and former lawyer in the Defense Department’s general counsel’s office. “When you’ve left office, you’ve left office. You can’t proclaim yourself to not be subject to the laws that apply to everyone else.”

It’s not clear from the affidavit whether Trump or anyone might face charges over the presence of classified records at Mar-a-Lago — 19 months after he became a private citizen — and FBI officials are investigating who removed the records from the White House to the Florida estate and who is responsible for retaining them in an unauthorized location.\

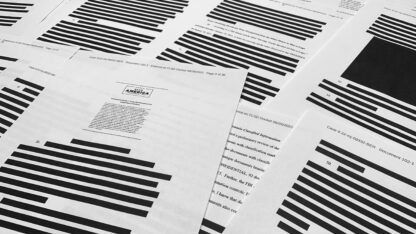

The FBI recovered 11 sets of classified records during the Aug. 8 search, and the affidavit made public Friday said 184 documents with classified markings also were found in 15 boxes removed in January. The Justice Department, responding to a Trump team request for a legal special master to sort through the materials, said Monday that officials had completed their own review of potentially privileged documents.

No matter the outcome of that latest issue, the affidavit makes clear that investigators are focused on potential violations of three felony statutes, including an Espionage Act provision that criminalizes the willful retention or transmission of national defense information.

Another law punishable by up to three years in prison makes it a crime to willfully remove, conceal or mutilate government records. And a third law, carrying up to 20 years imprisonment, covers the destruction, alteration or falsification of records in federal investigations.

The Espionage Act statute regarding retention of national defense information has figured in multiple prosecutions. Past investigations have produced disparate results that make it hard to forecast the outcome in the Trump probe. But there have been convictions.

Harold Martin, the ex-NSA contractor, pleaded guilty in 2019 to storing troves of classified information inside his home, car and storage shed, including handwritten notes describing the NSA’s classified computer infrastructure.

Which is why the Trump legal team may look to play up his status as a former president.

When it comes to handling government secrets, there are indeed some differences that could possibly be considered: Presidents, for instance, don’t have to pass background checks to obtain classified information, they’re not granted security clearances to access intelligence and they’re not formally “read out” on their responsibilities to safeguard secrets when they leave office.

“There’s no intelligence community directive that says how presidents should or shouldn’t be briefed on the materials,” said Larry Pfeiffer, a former CIA officer and senior director of the White House Situation Room. “We’ve never had to worry about it before.”

The May 25 letter from Trump attorney M. Evan Corcoran to Jay Bratt, the head of the Justice Department’s counterintelligence section, describes Trump as the leader of the Republican Party and makes multiple references to him as a former president.

It notes that a president has the absolute authority to declassify documents, though it doesn’t actually say — as Trump has asserted — that he did so with the records seized from his home.

It also says the “primary” law criminalizing the mishandling of classified information does not apply to the president and instead covers subordinate employees and officers.

The statute the letter cites, though, is not among the three that the search warrant lists as being part of the investigation. And the Espionage Act law at issue concerns “national defense” information rather than “classified,” suggesting it may be irrelevant whether the records were declassified or not.

Corcoran did not return messages seeking comment Monday.

It’s possible to “imagine a good faith mistake” or a president taking something sensitive without realizing it or because they needed it for a particular reason, said Chris Edelson, a presidential powers scholar and American University government professor.

But that argument could be complicated by the fact that the documents were not returned earlier in their entirety by Trump to the National Archives and Records Administration and that the FBI came to suspect — correctly — that there was still classified information at the property.

“I think if he had simply returned the documents right away, he’d be in a much stronger position legally,” Edelson said.

Ashley Deeks, a University of Virginia law professor and a former deputy legal adviser to President Joe Biden’s National Security Council, said in an email that the Trump team claims in the letter “seem to be more of a political argument than a legal argument.”

She added, “The president’s defense team seems to be trying to point out the magnitude of proceeding with this case rather than articulating a clear legal defense.”

Associated Press writer Nomaan Merchant in Washington contributed to this report.