Think before you snap that selfie.

That’s the serious message of a joint campaign created by two groups that have spent the past few years poking fun at problematic photos taken by Western volunteers. They often have the tendency to paint themselves as saviors to needy people in low-income countries.

The campaign, launched this month, offers guidelines and a cheeky video to first-time travelers or young volunteers eager to capture every moment of their vacation or mission on Facebook or Instagram. It was created by Radi-Aid, a project of the Norwegian Students’ and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH) that fights stereotypes in aid and development, and by Barbie Savior, an Instagram parody account.

According to the campaigners, the selfie takers may not realize that their posts, from the photo to the caption to the hashtags, can perpetuate stereotypes and rob the subject of dignity or privacy.

A seemingly innocent selfie with African kids, for example, can perpetuate the idea that only Western aid, charity and intervention can “save the world,” says Beathe Ogard, president of SAIH in Norway. These children are portrayed as helpless and pitiful, Ogard says, while the volunteer is made out to be the superhero who will rescue them from their misery.

Both Radi-Aid and Barbie Savior have gained a cult following for using satire and humor to tackle poverty porn, voluntourism and the white-savior complex. Radi-Aid, for example, made a viral video in 2016 titled “Who Wants To Be A Volunteer?” about a reality show whose grand prize is the chance to “Save Africa!” It has more than a million views.

Barbie Savior spoofs volunteer photography by recreating popular images using Barbie dolls and Photoshop. A recent entry portrayed Barbie sitting on a pit toilet. The caption: “Did you know that 112 percent of the people living in the country of Africa don’t have access to toilets? #squatitlikeitshot.” The account has more than 120,000 followers.

Despite their efforts, Barbie Savior and Radi-Aid have continued to observe “simplified and unnuanced photos playing on the white-savior complex, portraying Africa as a country, the faces of white Westerners among a myriad of poor African children, without giving any context at all,” Ogard says. The proliferation of these posts, she suspects, is the result of social media becoming a big part of how we communicate.

That’s what makes the guidelines so crucial, says Adeela Warley, CEO of CharityComms, a network of communications professionals working in U.K.-based nonprofits. “In the age of instant communications, it’s too easy to press ‘go,’ ” she says. “You still see so many images that make [impoverished people] look passive and helpless as opposed to empowered. People need to take the time to think about the stories their [social media posts] are telling.”

Ogard and the co-founder of Barbie Savior, Emily Worrall, hope that the guide will make young volunteers and travelers more aware of what they’re posting. Advice in the ten-point checklist includes: Be respectful of different cultures and traditions, avoid sweeping generalizations, challenge perceptions.

The campaigners also want photo-takers to question their own intentions. Are they just posting the photos for “likes”?

Worrall recalls her own experience a decade ago. When she was 17, she went on a volunteer trip to Uganda. She shared photos of herself and the orphans she was helping with her family and friends. They showered her with praise. “They told me, ‘Wow, you’re doing such amazing work.’ They put me on a pedestal,” she says. At the time, she didn’t consider the children’s privacy or vulnerability. Years later, it became inspiration for this Barbie Savior post:

That image is one of many cliched visual tropes that Ogard and Worrall have observed. They shared examples of the kinds of photos volunteers should avoid when traveling to the developing world:

Photos of volunteers giving candy or high fives to children.

These can give the viewer the impression that such small gestures can change a child’s life when “in reality it has no impact. A lot of these people make empty promises and never come back to the community,” says Worrall, who has worked in Uganda as a development consultant for seven years. She recreated the image for Barbie Savior in August 2016.

Photos of children on playgrounds.

“We’re constantly reproducing these images that have no respect for informed consent,” Ogard says. “In Norway, I would never show up at a school and take a selfie with kids playing.”

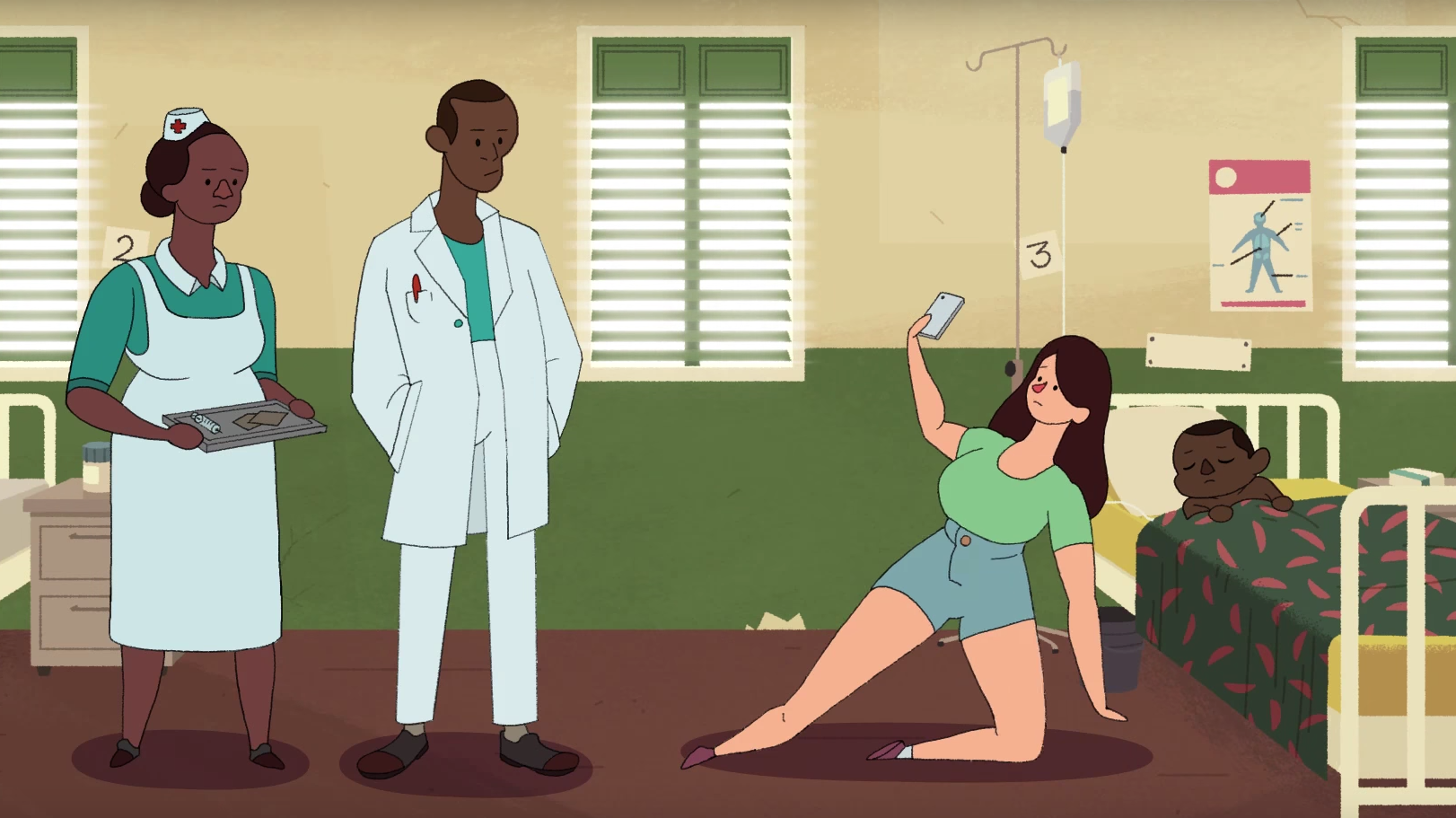

Photos of sick children in hospital beds.

The campaigners illustrate this point in their animated video. The young volunteer takes a selfie with a sick child in a hospital bed while bored hospital staffers look on. “It completely disregards the child’s needs,” Worrall says.

For years, communicators in the field of global development have been working to fight stereotype-reinforcing images in charity ads through awareness campaigns and codes of ethics. But few specifically address social media or are geared toward young people.

Susan Krenn is the executive director of Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Communication Programs, and her work centers on global development and public health programs overseas. While the university has a cultural orientation program for students traveling abroad, there are no hard and fast rules for how to portray their experience on social media. “I have not seen a resource like this,” she says of the guidelines. “We’d use it. It’s quite helpful, clear and easy.”

Ogard and Worrall don’t want the guidelines to discourage volunteers from posting photos on social media. They just want photo-takers to reflect on what they’re sharing. Ask for a subject’s consent, they say. Show your social followers something different.

If you need inspiration, Worrall says, check out some of the positive imagery from charities that received a Golden Radiator award in Radi-Aid’s annual contest for the best and worst charity ads. These ads, like those from an NGO called Mama Hope, show local people actively engaged in helping others in their community.

If you’re staying with a family in a low-income environment and they allow you to take a photo with their children, use it as a “great opportunity to challenge stereotypes,” Worrall says. That might mean providing details and context — names, locations, personal stories — in an extended caption on social media.

And if a child gets excited when they see you pull out your tablet or smartphone and ask to take a photo with you, that doesn’t mean it’s OK to do so. “It’s a cop out to say, well, they want it,” Worrall says. “A child can’t make that kind of decision.”

“Think of how they would view the photo if they found it at 25 years old,” she adds. “How would it make them feel?”

Your Turn

Have you ever felt conflicted about taking a selfie with children in low-income countries? Share your experience with @NPRGoatsandSoda on Twitter.

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))