Republican U.S. Senate nominee Herschel Walker commiserated as north Georgia farmers bemoaned environmental regulations and rising costs of doing business.

Minutes before, the former football star and political newcomer volleyed with journalists on issues ranging from gas prices to abortion.

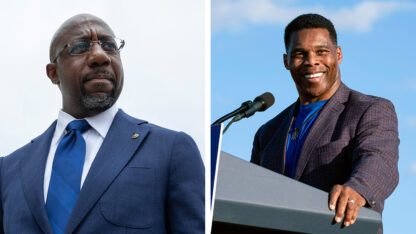

In both audiences, Walker tried every way he could to steer the conversation back to Sen. Raphael Warnock and a Democratic administration whose popularity lags in this battleground state that President Joe Biden won by the narrowest of margins.

“We need to be talking about what people are concerned about, that my opponent seems to be voting with Joe Biden rather than the people of Georgia,” Walker said at a north Georgia produce market. “That’s what we need to be putting headlines about what Herschel Walker is saying … because the people of Georgia are hurting.”

With generationally high inflation and Biden’s low popularity, Republican candidates across the U.S. are spending this election year similarly trying to keep the focus on Democrats.

But for Walker, the sweeping partisan jabs on display at multiple campaign stops this week offered a chance to steady an otherwise haphazard campaign.

Some Republicans quietly acknowledge that such deflection may be the only way Walker can win this midterm contest that will help determine control of a Senate now split 50-50 between the two major parties.

“Look, it’s not how many times you get knocked down, it’s how many times you get back up,” said state Sen. Butch Miller, as he campaigned with Walker in north Georgia.

Walker, 60, cruised to the GOP nomination in May, mostly on his celebrity status as the star running back on the University of Georgia’s national championship football team in 1980 and his personal friendship with former President Donald Trump.

But along the way, Walker has faced new disclosures on past violent threats against his first wife.

He’s exaggerated his academic and business records, and alternately denied ever making such statements.

He acknowledged fathering multiple children he hadn’t publicly mentioned previously despite spending decades blasting absent fathers.

And Walker recently was captured on video at a closed campaign event offering a nonsensical explanation of the climate crisis as China sending its “bad air” to the U.S. while stealing “our good air.”

Warnock’s campaign and allied Democratic campaign arms reacted with an advertising onslaught casting Walker as unqualified.

“Every one of Walker’s likes, scandals and bizarre statements proves that he isn’t ready to represent to represent the people of Georgia and can’t be trusted to serve in the U.S. Senate,” said Dan Gottlieb, a spokesman for the Georgia Democratic Party.

All of that played out as Warnock has raked in campaign cash — more than $17 million in the second quarter of 2020 and $70 million-plus for the cycle.

That has allowed the senator to develop a personal brand that positions him well ahead of Biden among Georgia voters and mutes any Republican contention that 2020 was an aberration in the state.

Just a few cycles ago, any Republican nominee would have been a prohibitive favorite in a midterm Senate election here, regardless of economic conditions or who occupied the White House.

Instead, decades of growth, concentrated in metro Atlanta, have yielded a politically, racially and ethnically diverse population more open to electing Democrats.

Trump’s underperformance among college-educated whites accelerated the shift, as did Democrats’ organizing efforts.

That led to Biden outpolling Trump by about 12,000 votes out of 5 million cast — a record November turnout for Georgia.

Warnock followed with a wider margin in a January special election runoff: 94,000 votes out of almost 4.5 million cast, a record runoff turnout.

Republicans have answered Walker’s stumbles with an influx of experienced aides for the first-time candidate and visits to the state by national Republican operatives.

Walker aides said the coming weeks will be built around various policy themes, with targeted attacks on Warnock.

It’s not so much a campaign reset, the aides said, since mid- to late summer is nearly always when general election campaigns ratchet up.

But it’s an effort clearly aimed at changing the narrative around the matchup. The opening salvo was agriculture. Public safety and crime come next. The economy will follow.

Walker himself talked this week of “listening sessions” built around policy topics. He showed some evidence of those sessions in turning most any topic back to Warnock, Biden and the economy.

“Terrible, terrible leadership,” he called it, adding that working-class Georgians “know it’s not right.”

He demonstrated an increasing familiarity with the details of Warnock’s record when he blasted the idea of suspending the federal gas tax, something the senator proposed. Walker called that “the hero effect … I cause the problem and then you call me to come put it out.”

Yet there were flashes of the tangents and falsehoods that have drawn negative attention already.

At a livestock auction outside Athens, Walker again denied he ever said he’d graduated from the University of Georgia, accusing his questioner of being a “Raphael Warnock guy.” Walker has made such claims on video; he never graduated. Later, Walker essentially committed to debate Warnock in October, only to have his campaign follow up with a series of conditions.

In a discussion about immigration, Walker offered bromides about the U.S. needing “legal immigration,” only to have Miller step in to talk about specific visa programs. In a roundtable on agriculture, Miller and Terry Rogers, a former state representative, again filled in many details.

When farmers complained about the Biden administration’s advocacy of electric farming vehicles, Walker didn’t just focus on cost but questioned the technology itself. “It’s only gonna run for a certain amount of time,” he said. “You gotta charge it for eight hours. You’ll never get any work done.”

Miller downplayed any cumulative damage to Walker’s prospects but said it’s critical for the Republican nominee to crystallize his case against Warnock and weave in his own biography more effectively.

“One of his strongest virtues is his relatability to people, and he’s getting out and doing that,” Miller said. As for broader attacks about inflation and the economy, Miller added, Walker has a convenient ally: “It’s all true.”