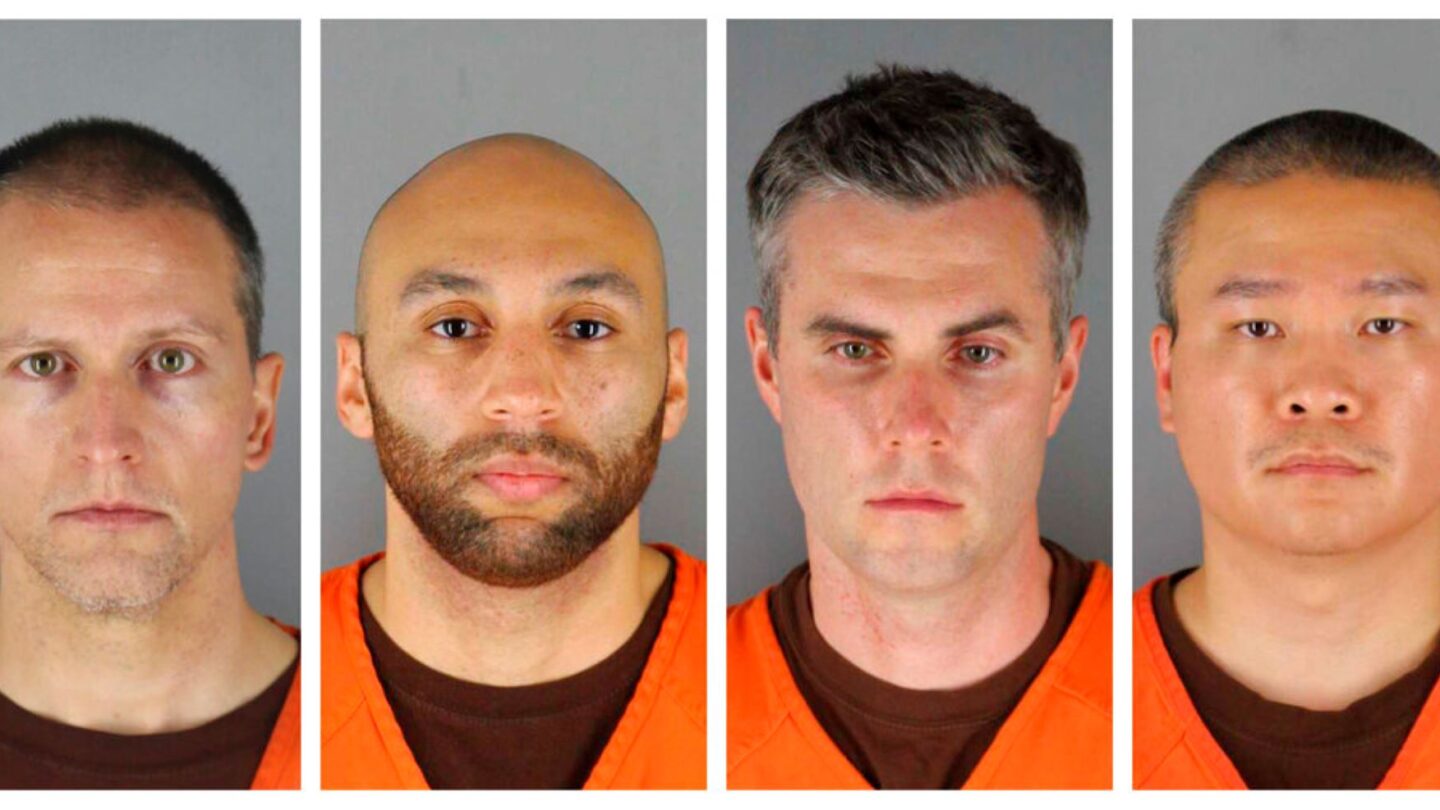

Now that former Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin has been sentenced to federal prison, attention turns to the fates of three fellow ex-cops who are still working their way through a complicated web of state and federal court proceedings arising from the killing of George Floyd.

Tou Thao, J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane still await sentencing for their convictions on federal civil rights charges in February. Lane awaits sentencing in state court after pleading guilty to a reduced charge there, while Thao and Kueng are scheduled to stand trial in October on state charges of aiding and abetting both murder and manslaughter.

Kueng and Lane helped restrain Floyd while Chauvin, who is white, killed Floyd by kneeling on his neck for nearly 9 1/2 minutes despite the handcuffed and unarmed Black man’s fading pleas that he couldn’t breathe.

Thao helped hold back an increasingly concerned group of onlookers at the scene outside a Minneapolis convenience store where Floyd tried to pass a counterfeit $20 bill in August 2020.

Here’s a look at what’s still to come in the legal process that has flowed from a killing that led to worldwide protests and a national reckoning on racial injustice:

CHAUVIN’S FUTURE

U.S. District Judge Paul Magnuson sentenced Chauvin on Thursday to 21 years in prison on federal civil rights charges — 20 years stemming from Floyd’s killing and a year more arising from Chauvin’s earlier assault on a 14-year-old boy.

With credit for seven months served, Chauvin still has 20 1/3 years to go — 245 months — on his federal sentence, plus five years of supervised release after that.

As of Friday, Chauvin was still in the state’s maximum security prison at Oak Park Heights, where he’s been held since his conviction in state court last year for murder and manslaughter, which got him a 22 1/2 year sentence.

His state and federal sentences are running concurrently. But because of differences between state and federal parole rules, he’ll actually serve a little more time behind bars on the federal sentence than he faced under his state sentence alone.

Chauvin knew that when he accepted a plea deal on the federal charges in December. But he presumably considered that preferable because he’s been kept in solitary confinement in the state prison for his own safety. If he’d been in the general population at a state prison, he would have run the risk of running into people he had busted.

Magnuson expressed hope at Thursday’s sentencing that the Bureau of Prisons will keep him under easier conditions, and not too far from his family in Minnesota and Iowa. But his placement is up to the bureau, which could take weeks to move him.

While Chauvin gave up his right to appeal his federal conviction, his appeal of his state conviction is pending. He also faces a pair of federal civil rights lawsuits.

NEXT FEDERAL SENTENCINGS

Magnuson has not set sentencing dates for Thao, Kueng and Lane, who remain free on bail. Federal prosecutors have already asked the judge to give Thao and Kueng sentences that would be shorter than Chauvin’s, but “substantially higher” than the 5 1/4 to 6 1/2 years they’re seeking for Lane.

Thao’s attorney, Robert Paule, is seeking a sentence of two years. The recommendation from Kueng’s attorney, Thomas Plunkett, remains sealed and Plunkett did not immediately return a call seeking comment Friday.

Lane’s attorney, Earl Gray, has asked for 27 months, which if granted would let Lane go free after two years. That’s about when Lane would become eligible for release on his recommended state sentence.

Lane’s plea agreement on a state charge of aiding and abetting manslaughter calls for three years. Under Minnesota’s system, assuming good behavior, inmates are entitled to parole after two-thirds of their sentence; in the federal system they become eligible after 85%.

Magnuson expressed some sympathy for the three Thursday, when he told Chauvin, “You absolutely destroyed the lives of three young officers by taking command of the scene.” But evidence presented at their trial established that they failed to stop Chauvin while they could still have saved Floyd’s life. Magnuson gave Chauvin a little break by imposing a sentence that was lower than what prosecutors sought, but did not indicate how he’d treat Thao, Kueng or Lane.

UPCOMING IN STATE COURT

Hennepin County District Judge Peter Cahill has scheduled Lane’s sentencing for Sept. 21. Prosecutors and Gray are jointly recommending three years. He would serve that at the same time as his federal sentence, and in federal prison.

Cahill has set the trial for Thao and Kueng, who rejected offers of plea agreements earlier, to begin Oct. 24. But his order left open the possibility that deals could still be reached. He said the court would not accept a plea bargain unless the change-of-plea hearing was scheduled for “not more than 15 days” after the defendants’ federal sentencings.

If Thao and Kueng go to trial, a major difference from Chauvin’s will be that most proceedings won’t be televised or livestreamed.

Cahill made a rare exception for Chauvin’s trial due to the dangers of COVID-19. But he ruled that the risks from the pandemic have abated to the point that he’s bound by the state court system’s normal restrictions on cameras, which allow them in “pre-guilt” phases only when all parties consent, but are easier for sentencings.

Minnesota Chief Justice Lorie Gildea was impressed enough with how smoothly live audiovisual coverage worked during Chauvin’s trial that she asked a court advisory committee to consider whether the rules should be loosened.

But a divided panel recommended in its final report last week that there be no major changes. Any liberalization would be up to the Minnesota Supreme Court, but there’s no deadline for a decision.