Hundreds of millions of dollars are flowing into Georgia as part of the opioid drugmaker settlement between states and top opioid manufacturers, distributors and pharmacies. The more than $50 billion nationwide payout is designed to help communities address the ripple effects of the opioid crisis.

Nationally, the crisis saw nearly 107,000 Americans die from a drug overdose in 2021 alone, with most deaths linked to an opioid, according to the CDC.

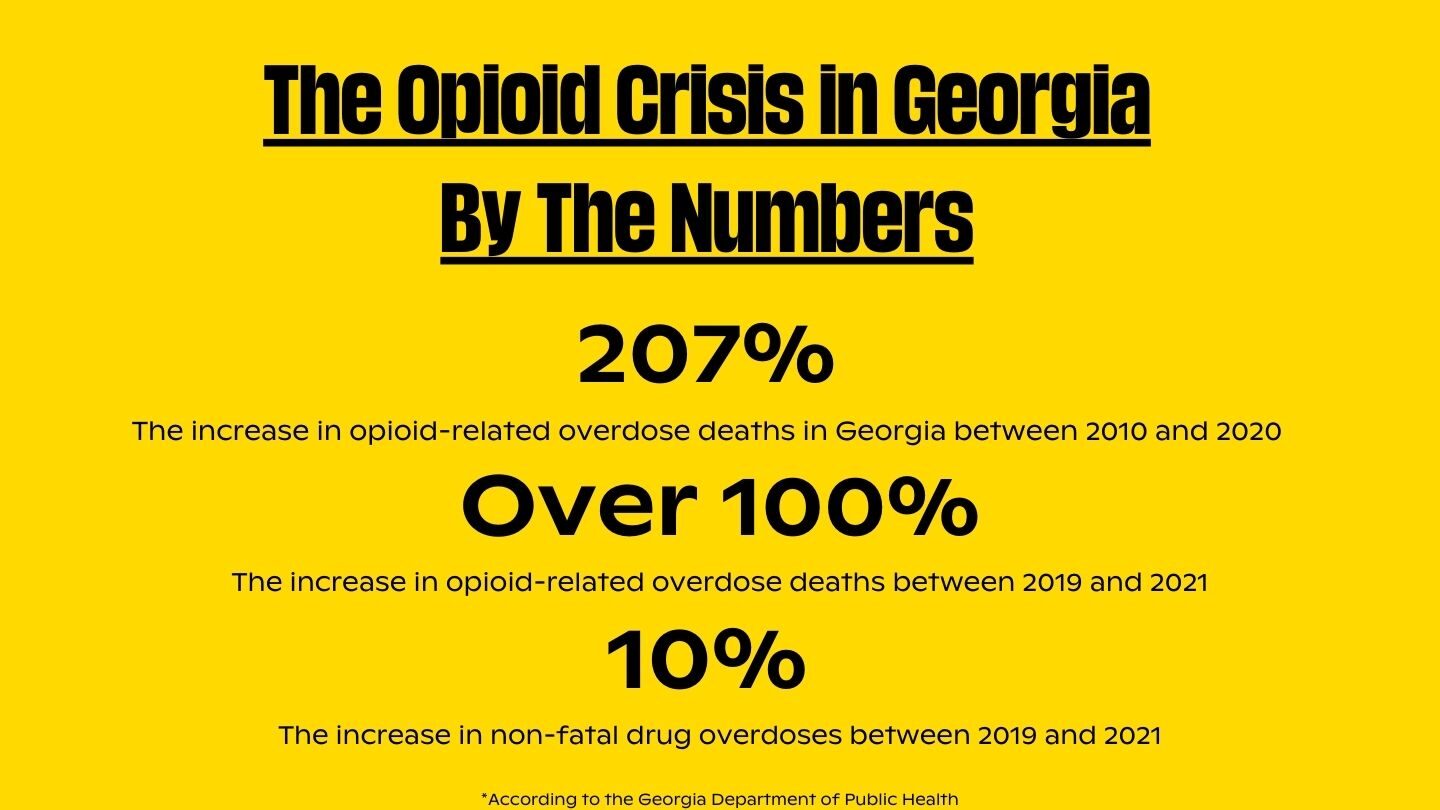

The numbers are equally staggering in Georgia, fueled mostly by the highly potent synthetic opioid painkiller fentanyl.

So what does the opioid settlement mean for Georgia? How much money is coming to the state, how will it be spent and who gets to decide?

Mental health advocates, state and local officials have touted the settlements as providing desperately needed relief to communities hit hard by the crisis.

The state urgently needs the settlement money, said Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities Commissioner Kevin Tanner.

“Across Georgia, addiction touches every family in some way. We all have a family member or a loved one or someone we know in our work community or our church community who has been touched by addiction,” he said.

“And I think that by implementing the opioid settlement and by building out a continuum of care, we’re going to have a positive impact on all of those that have struggled with addiction. But we’re also going to be able to create more opportunities for recovery,” he added.

Tanner is leading the administration of Georgia’s opioid settlement fund.

A top priority is expanding more peer-led recovery programs that include the expertise and participation of so-called “peers” — people with lived experienced with addiction, treatment and recovery.

And advocates have clamored for a seat at the table.

So far, Georgia lags behind nearly half of the states, which have already announced their protocols for how community organizations can apply for a share of settlement funds.

So what’s next?

Tanner said the state expects to announce detailed distribution plans within the next three months.

This includes unveiling a new website and grant application portal, and a policy document laying out the state’s guardrails to ensure funds are awarded within the requirement of the settlement agreement.

“Creating a vision of what Georgia needs to look like 18 years from now, when the last settlement dollar comes into the state, and laying a plan to get us there is the first step,” Tanner said.

Georgia’s agreement mandates settlement funds are spent on “approved purposes,” including addiction prevention, harm reduction, treatment and recovery services.

If the state suspects funds are being used for a non-approved purpose, it can request documentation from regional officials on use of the funds. And the agreement includes an appeals process.

Who decides?

The state’s memorandum of understanding requires local governments to establish advisory councils that would help determine settlement spending in their region.

The councils are required to include a member from a participating county’s board of health, an executive team member of a Community Service Board, and a sheriff’s department representative.

WABE health reporter Jess Mador and deputy managing editor Molly Samuel discuss Georgia’s opioid settlement funding

Following the money

Attorney Christine Minhee is trying to make following the settlement money easier.

In 2019 she founded the project OpioidSettlementTracker.com to monitor and analyze opioid settlement spending across the country.

It’s a clearinghouse of sorts, providing information she said she hopes helps advocates, governments and community groups better understand the settlement, and how its funds are spent.

“The settlement agreements between the lines imply that the political process, on the part of the state, will largely control the nature and texture of opioid settlement spend,” she said. “And the decision to give moneys to governments and to prioritize public litigants over the private ones is of huge concern and debate.”

Most of the nationwide settlement is intended to go to governments to help address the impacts of the opioid crisis and prevent similar crises in the future. But not all states plan to report where all of their funding is spent.

This includes Georgia, which has promised to publicly report on the distribution of the state’s 75% share of the money.

Minhee wants to see more public reporting nationwide.

“I do think that in order to get the clear picture of how these settlement dollars are spent, more states need to step up and volunteer to publish their opioid settlement expenditures, or else we’re just going to have an increasingly polarized discussion on how these settlement dollars should be spent and whether or not they’re being spent well,” she said.

Georgia’s opioid settlement plan does not require local governments to publicly report their 25% share. It also sets aside a percentage of local funds for county sheriffs’ use for “approved purposes.”

The state’s plans require an annual report on settlement spending that includes the allocation of any approved funding awards, recipients, programs funded and disbursement terms.

The report is also required to include an assessment of how well settlement funding has been used to abate opioid addiction, overdose deaths and other consequences of the opioid crisis.

Lessons from Big Tobacco

Minhee points to lessons learned from states’ handling of money from the 1998 Big Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, the largest civil litigation settlement in United States history.

The master $246 billion agreement with tobacco companies and state attorneys general settled dozens of state lawsuits over the healthcare costs associated with smoking-related diseases.

Studying the tobacco settlements is what motivated Minhee to launch the Opioid Settlement Tracker, she said.

“It all started out with my dorky interest in the Big Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement,” she said. “The paradigmatic complaint of that Big Tobacco era of things is that less than 3% of the moneys were spent on the reasons why state attorneys generals went out to sue in the first place.”

Funding from the settlement was intended to help states recoup costs related to cancer and other smoking-related illnesses, expand public health programs for smoking cessation, education and prevention, and to change the way cigarettes could be advertised and marketed.

Christine Minhee discusses the Opioid Settlement Tracker on “All Things Considered”

According to the American Lung Association, many states established such programs. But many did not fund them at the levels recommended by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Georgia’s share of the Master Settlement Agreement amounted to more than $3 billion. There was little transparency written into the state’s plans for using the money.

And few guardrails, said Professor Nanette Turner, associate dean and professor at the College of Health Professions at Mercer University.

“The dollars came into the state without very specific guidelines that it must be used for these purposes. And so anytime that happens, I think that probably is true in any state, if you don’t set aside the guidelines before you actually get the money, then you’re going to see it being used for whatever the lawmakers feel like they need the money for at any given time,” said Turner. “And that’s what happened with those tobacco dollars. They weren’t specified specifically for public health purposes.”

Georgia, for example, used some of its settlement money to pay for rural sewer and water projects, a U.S. Government Accountability Office report found.

Another key problem, said Minhee, is that the Big Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement didn’t require states to spend a minimum percentage of their funds on public health interventions.

She is hopeful that states’ opioid settlements would be better positioned from the outset, at least.

“So going into this opioid context, I think a lot of folks saw a minimum threshold percentage of abatement spend as a no-brainer inclusion,” Minhee said.

Community involvement makes a difference

With the lessons of the tobacco settlement in mind, Turner urges advocates and people directly affected by opioids, overdose and recovery to get involved as opioid settlement money is distributed in their communities.

“They really need to put the the guardrails on early in the process because it’s hard to change that once you’ve gone down the road and it loses its newness, if you will, its urgency in people’s eyes and they move on to the next thing,” Turner said.

“These kinds of health issues require long-term commitments of resources in order to see the needle change down the line. You’ve got to be committed to these resources over a long period of time to see the change.”

Jim Burress, Christopher Alston, Lisa Rayam and Lily Oppenheimer contributed to this report.