“What did it mean that we had a Black History Month,” he started to wonder.

“And what would it mean if we didn’t?”

Why did Carter G. Woodson come up with it?

Talk to any group of historians about the meaning of Black History Month and they will all mention the same name: Carter G. Woodson.

“We call him the father of Black history,” says Diana Ramey Berry, chair of the history department at The University of Texas, Austin.

In 1926, Woodson founded Negro History Week — which would grow into what we now know as Black History Month.

“The idea was to make resources available for teachers — Black teachers — to celebrate and talk about the contributions that Black people had made to America,” says Karsonya Wise Whitehead, the founding executive director for the Karson Institute for Race, Peace, and Social Justice at Loyola University. Whitehead is also a former secretary of ASALH — the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, which Woodson founded in 1915.

Woodson picked the week in February marked by the birth of Abraham Lincoln and the chosen birthday of Frederick Douglass, because those days were celebrated in his community. In this way, Woodson built on a Black tradition that was already commemorating the past.

“He also understood that for Black students, to see themselves beyond their current situation, they had to be able to learn about the contributions that their ancestors had made to this country,” Whitehead says.

The historical context of the moment is also key, according to Berry. “African Americans were, 50 or so years outside of slavery and trying to figure out their space in the United States,” she says.

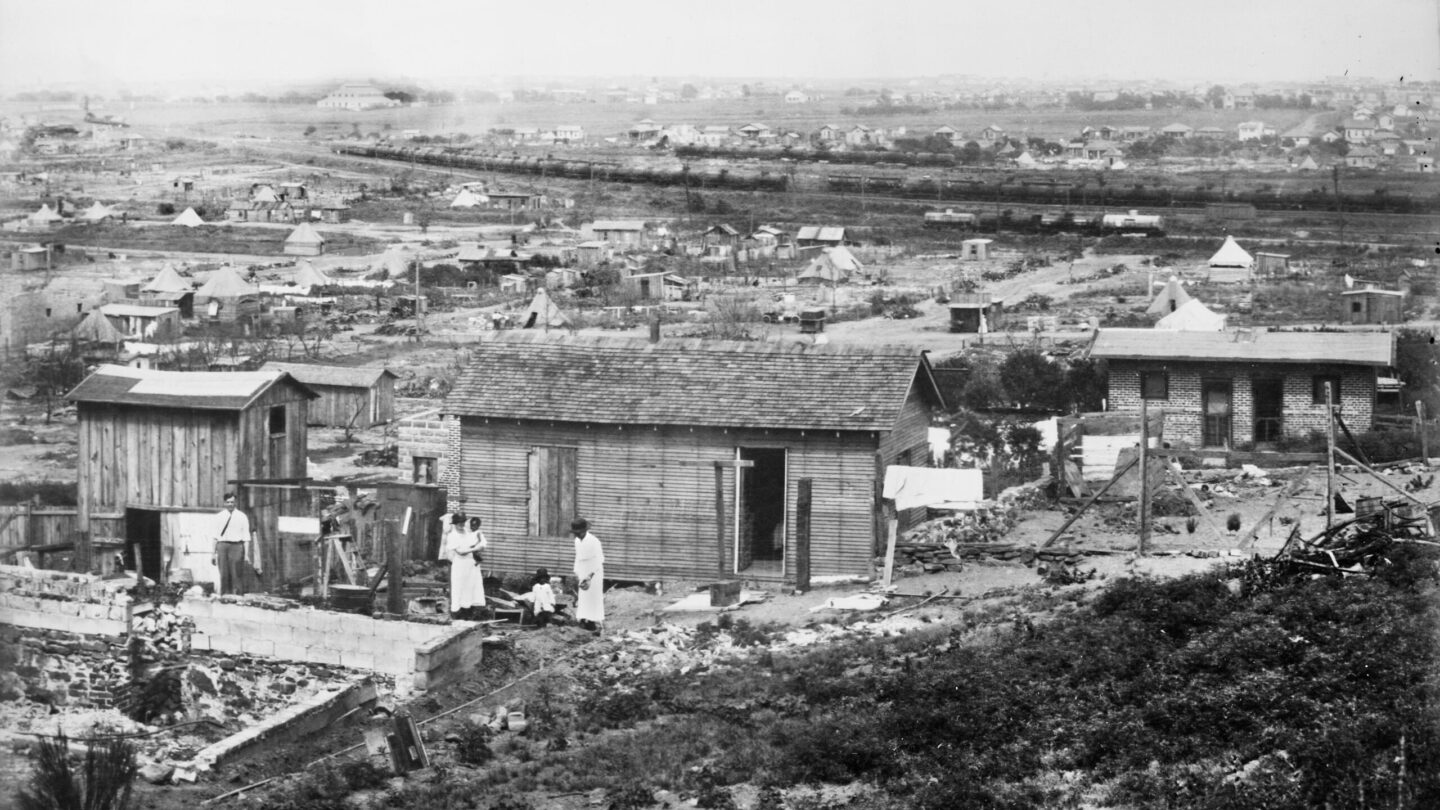

That space was being violently demarcated by white supremacy. “We were experiencing segregation, lynchings, mass murders and massacres,” says Berry. A few years before was 1919’s so-called Red Summer, when white mobs attacked Black neighborhoods and cities. Then in 1921 came the Tulsa race massacre.

Alongside white supremacist violence was an attempt to whitewash U.S. history, excluding both the contributions and the realities of Black people. This was the period when statues of confederate soldiers were erected and the lost cause myth — the lie that the Civil War was about preserving a genteel way of life and that slaves were well treated — was becoming a dominant narrative. “Not just in the South,” says Hasan Kwame Jeffries, a professor of history at The Ohio State University.

“A complete revision and distortion of the Civil War, of slavery, of emancipation, of reconstruction was being deeply embedded into the American public education system,” he adds.

“Let’s talk about Black people”

By the time he was growing up in New York City public schools in the 1980s, Jeffries says Black History Month felt very much like, “let’s talk about Black people for a couple of days.”

“It was the usual cast of characters,” he says. Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, a couple of Black inventors — “and then we’d move on.”

Says Whitehead, “In school, all of a sudden everything became about Black people, right?”

“So you’re putting your Mac and cheese and collard greens into the cafeteria. You’re lining the halls with all this Black art that would then get taken down when February ended,” she says.

Black History Month may sometimes feel tokenizing, but it is still necessary, says Whitehead. “You can go to places,” she says rattling off state names, “where if you didn’t have Black History Month, there would be no conversations at all.”

What we need is an inclusive — and accurate — American history, according to Berry. But American history remains a segregated space. “When you go into American history courses, many of those courses are taught from the perspective of just white Americans and students,” Berry says.

The paradox of Black History Month today, Whitehead says, is that we still need it, even if it is not enough. “We want Black history to be American history,” she says. “But we understand that without Black History Month, then they will not teach it within the American history curriculum.”

Which brings us back to Tilghman, and an answer to his question: What would it mean if we didn’t have Black History Month?

“If, but for Black History Month, those stories wouldn’t be told,” Tilghman says, “then we have a larger problem that is not Black History Month. And that’s not actually a reason to keep Black History Month.”

“That’s a reason to fight for something better than Black History Month.”

Parallels to Woodson’s Time

There have been efforts in some states, and in some curriculums to integrate American history across the year, making slow steps forward. But Hasan Jeffries says the moment we are in right now acutely parallels the time period in which Carter G. Woodson founded Negro History Week and January 6th. Once again, at the center of all of this, is a battle over who gets to control history.

“We see that same pushback now with this divisive subjects and divisive issues stuff,” Jeffries says, referring to “divisive topics” laws in Republican-led states that ban acknowledging that America was founded on racist principles.

“If we can just trot out Rosa Parks sitting on a bus and then put her back on the bus and not talk about it, that’s fine,” says Jeffries. “But we don’t want to talk about the society as a whole that supported and embraced Jim Crow. And the way in which inequality is literally written into the U.S. constitution.”

Integrating Black history into American history isn’t some simple act of inclusion, Jeffries says. You can’t just insert Black people who invented things, or made notable contributions, into a timeline, he says.

“You start having to question what you assume to be basic truths about the American experience, the myth of perpetual progress and American exceptionalism — all that crumbles,” Jeffries says.

But change is coming, he notes.

The undergraduates Jeffries teaches don’t necessarily begin with a full grasp of U.S. history, but many are now showing up in his class precisely because they feel they haven’t been told the whole story.

“They’ve been seeing all this happen over the last four or five years — the rise of racism, white supremacy and hate,” he says of some of his white students. “And they’re coming to college saying, okay, something ain’t right.”

Feeding the appetite for robust history

That hunger for Black history, for robust American history, is something high school teacher Ernest Crim III has tapped into on social media. His tiktok videos about Black figures in history have gone viral, racking up tens of thousands of views. One of those videos was about Carter G. Woodson, and the origins of Black History Month.

Crim is a Black teacher teaching Black, Latino and white students in a Chicago suburb, which means in a lot of key ways he is similar to the teachers Woodson created Negro history week to serve. “Woodson created Negro History Week with a particular purpose,” Crim says. “So that we could come together and discuss what we’ve been doing all year round, not to celebrate it for one week, which eventually became a month.”

Which is why in Crim’s history classroom, February isn’t the only time they talk about people of color. “In every unit of study I look for examples of what Black people and Latino people were doing at that time,” he says.

“We’ll get to the civil rights unit in my class, probably in March,” he says. “They going to think it’s February, with how much we’re talking about Black people.”

For Crim, in the teaching of history, separate is not equal.

Illinois, where he teaches, does not have a divisive topics law, but even without an outright ban, he says a lot of his students aren’t learning about systemic racism in American history. “Even though every state isn’t banning it, there’s no need to because most history teachers don’t really do it at all,” Crim says. You don’t need to ban something that is not really taught in the first place.

Teaching history, teaching integrated honest history, can be transformative, Crim says. “It’s about changing your thoughts and that can change your entire generation. That can change your family. That could change, just the trajectory of your entire life,” he says.

“The story that we as Americans tell about who we were, that story tells us who we are,” says Shukree Tilghman.

Tilghman’s campaign to end Black History Month left him with a renewed respect for the rich history of the month itself. In the past few years it may seem like history has resurfaced as a battleground of American identity, but it’s always been that way. “History is about power,” Tilghman says, “and who has the power to tell the story.”

Black History Month, at its best, has the ability to crack open the door to a kind of narrative reparations, says Hasan Jeffries. “I mean, that’s part of the power of Black History Month. It holds America accountable for the narrative that it tells about the past.”

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))