In a pivotal election year, U.S. democracy continues to face a persistent challenge among the country’s electorate — gaps in voter registration rates between white eligible voters and eligible voters of color.

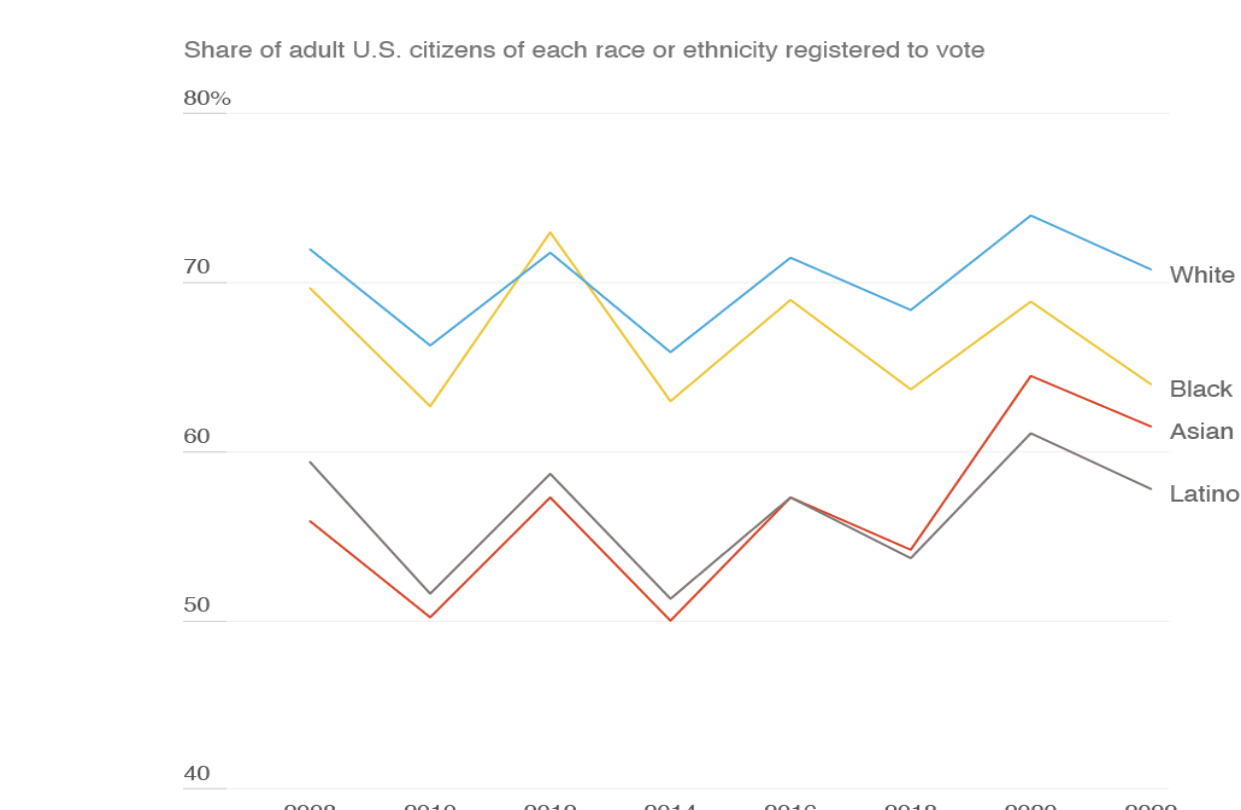

For years, the shares of Black, Asian and Latino citizens age 18 or older signed up to cast ballots have trailed behind that of white adult citizens, according to the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey.

And while the estimated registration rate for Black eligible voters has stayed closer to (and, in 2012, even surpassed) the rate for white eligible voters, the rates for Asian Americans and Latinos — who make up the country’s top two fast-growing electorates by race or ethnicity — have remained among the lowest of the racial and ethnic groups in the United States.

Based on national estimates from the last two federal election years, the disparity in registration rates between white and Asian eligible voters is around nine percentage points. Between white and Latino eligible voters, the gap is about 13 percentage points.

Long-standing barriers to voter registration have made it difficult to close these gaps, and dedicated investment is needed to ensure fuller participation in elections and a healthier democracy, many researchers and advocates say.

“This is something that needs to be paid attention to sustainably all the time,” says Rodrigo Dominguez-Villegas, director of research at the UCLA Latino Policy & Politics Institute. “It is not something that should be paid attention to only when we are getting close to a presidential election.”

For some, economic needs overshadow political participation

Many Latino and Asian American eligible voters are naturalized U.S. citizens, and that, Dominguez-Villegas says, can make it more difficult to figure out how to get registered to vote, especially in states that don’t offer automatic voter registration or same-day registration.

“They need to learn the ropes of the political system at the same time as they are learning everything else about living in a different country,” says Dominguez-Villegas.

Dominguez-Villegas, who co-wrote a report about the lower voter registration rate for Latinos in the 2020 elections, points out that while more states started allowing early in-person and mail voting after the COVID-19 pandemic began, it can be hard for some eligible voters to “prioritize political participation over their day-to-day economic needs” when they’re working lower-wage jobs.

“There are some types of jobs that might be preventing people from being able to even take time off work to vote. And so when people know that they’re not going to be able to exercise the right to vote, they are a lot less inclined to even register for it,” Dominguez-Villegas says.

It’s a kind of barrier that Vivian Chang, executive director of the Philadelphia-based advocacy group Asian Americans United, says community organizers have encountered when trying to promote voter registration in and around the city’s Chinatown neighborhood.

“A lot of folks are just struggling to survive,” Chang says. “Voting is a very separate thing. And honestly, it’s a part of an institution that for them is not one that necessarily values them.”

Asian Americans and Latinos are less likely to be contacted by campaigns

Still, low registration rates among Asian Americans and Latinos should not be seen as a sign of low interest in U.S. politics, warns Taeku Lee, a professor of government at Harvard University.

“An old narrative has been, because these groups are predominantly first- and second-generation Americans, that they’re more interested in the politics of their home country than they are in the politics of the United States, or they’re groups that like to keep their head down and stay out of politics,” says Lee, whose research focuses on racial and ethnic politics. “I think they are every bit as invested in what politics can do to them or do for them.”

The shortcoming lies in large part with the country’s major political parties, Lee argues.

“There’s a long-standing view that you don’t target precious campaign resources towards groups that you consider to be low-propensity voters. And if a group like Asian Americans are predominantly naturalized citizens and a large group of them are potentially first-time voters, then you’re likely to be seen as a low-propensity voter,” Lee says.

According to a Pew Research Center survey, Asian Americans and Latinos were among the least likely to say that a political candidate’s campaign or a group supporting a candidate contacted them in the run-up to the 2020 general election.

Voting restrictions can disproportionately affect people of color

In some states, restrictive voter ID requirements that disproportionately affect many eligible voters of color have also put in place systemic barriers to voter registration, Lee points out.

In 2020, Latinos and Asian Americans who were eligible to vote, for example, were more likely than white eligible voters not to have a current driver’s license, and Latinos were more than twice as likely as people who identify as white and not Latino not to have any government-issued photo ID that was not expired, according to a report by the University of Maryland’s Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement and the voter advocacy group VoteRiders.

“Some of the state-led election reform initiatives, like voter identification laws, are really critical in understanding whether or not the hard-won gains of the Selma, Ala., march in 1965 really continues to be part of our long-standing history of wins and losses in terms of political rights and political freedom,” says Lee, referring to the historic civil rights demonstration that galvanized Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

That landmark law led to significant increases in the registration rates for Black eligible voters in the South, while also sparking a surge in voter registration among white eligible voters in some areas, which some researchers interpret as signs of white opponents of the Voting Rights Act counter-mobilizing in response.

“Citizenship rights are not something that you can really simply take for granted or ignore, but they are rights of citizenship that can be expanded or that can be contracted depending on the politics of the day,” Lee adds. “And the politics of today is a politics where there are organized forces that are aiming to further contract those rights of citizenship for groups like Latinx and Asian Americans.”

“…without our voice, nothing’s going to be done”

At the local level, community organizers are trying to boost registration rates with campaigns that include visits to senior centers, supermarket parking lots and outside public assistance offices.

“It takes a long time to change people’s minds about how voting is important,” says Wei Chen, Asian Americans United’s civic engagement director, who recently stopped by an adult day care center about a 10-minute drive north of Philadelphia’s Chinatown.

Speaking in the Chinese dialects of Mandarin and Cantonese, Chen demonstrated how to navigate one of the city’s voting machines, which — because of a Voting Rights Act requirement — must display touch-screen menus in Chinese and Spanish in addition to English.

“We are fighting for language justice. Providing information and having materials there is not enough,” says Chen, who sees language access as a particularly challenging barrier to voter registration for eligible voters with low literacy skills. “We need them to hire people who speak our language.”

Less than two hours northwest of Philadelphia, Katherine De Peña has been trying to stop eligible Spanish-speaking voters with a friendly “hola” on the sidewalks of downtown Reading, Pa., home to growing Puerto Rican, Dominican American and Mexican American communities.

With a tablet computer in hand, De Peña, a field organizer in charge of Make The Road Pennsylvania’s voter registration program, is ready to make a practiced pitch.

“Most of them say, ‘I’m not voting because it doesn’t change anything,’ ” De Peña explains. “And I say, ‘OK, but nothing is going to change if you don’t do anything. So this is the way you have to do it.’ “

Jose Cruz-Hernandez was sold.

“It’s very important that people know to vote because without our voice, nothing’s going to be done,” Cruz-Hernandez says after De Peña walked him through in Spanish how to register to vote on her tablet while he took a break from rushing to meet his daughter.

Not having enough time to spare was the main reason he hadn’t signed up before. “I have to take care of my daughter,” Cruz-Hernandez says. “I have to do a lot of things.”

Now with his application submitted, De Peña is one voter closer to a higher registration rate for Latinos.

“Don’t you worry. We got this like within five, 10 years,” De Peña says with a hearty laugh. “Yeah, it takes time.”

Edited by Benjamin Swasey

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))