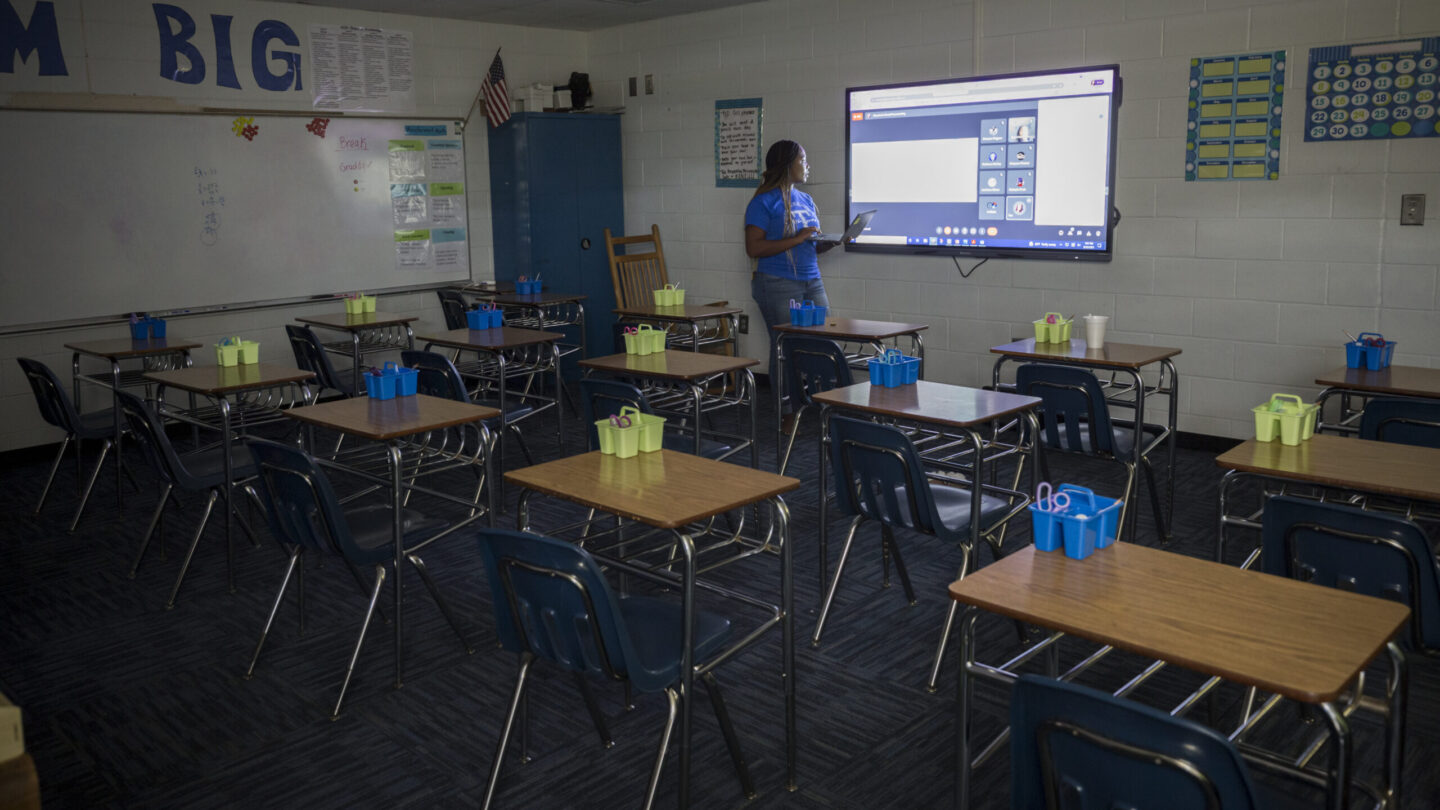

As schools across the South grapple with teacher shortages, many are turning to candidates without teaching certificates or formal training.

Alabama administrators increasingly have hired educators with emergency certifications, often in low-income and majority-Black neighborhoods. Texas, meanwhile, allowed about one in five new teachers to sidestep certification last school year.

In Oklahoma, an “adjunct” program allows schools to hire applicants without teacher training if they meet a local board’s qualifications. And in Florida, military veterans without a bachelor’s degree can teach for up to five years using temporary certificates.

Decisions to put a teacher without traditional training in charge of a classroom involve weighing tradeoffs: Is it better to hire uncertified candidates, even if they aren’t fully prepared, or instruct children in classes that are crowded or led by substitutes?

“I’ve seen what happens when you don’t have teachers in the classroom. I’ve seen the struggle,” Dallas schools trustee Maxie Johnson said just before the school board approved expanding that district’s reliance on uncertified teachers. He added, “I’d rather have someone that my principal has vetted, that my principal believes in, that can get the job done.”

A Southern Regional Education Board analysis of 2019-20 data in 11 states found roughly 4% of teachers were uncertified or teaching with an emergency certification. In addition, 10% were teaching out of field, which means, for example, they may be certified to teach high school English but assigned to a middle school math class.

By 2030, as many as 16 million K-12 students in the region may be taught by an unprepared or inexperienced teacher, the group projects.

“ The shortages are getting worse and morale is continuing to fall for teachers,” said the nonprofit’s Megan Boren.

In Texas, reliance on uncertified new hires ballooned over the last decade. In the 2011-12 school year, fewer than 7% of the state’s new teachers — roughly 1,600 — didn’t have a certification. By last year, about 8,400 of the state’s nearly 43,000 new hires were uncertified.

The trustees in Dallas leaned into a state program that allows districts to bypass certification requirements, often to hire industry professionals for career-related classes. The school system has hired 335 teachers through the exemption as of mid-September.

In Alabama, nearly 2,000 of the state’s 47,500 teachers didn’t hold a full certificate in 2020-21, the most recent year for which data is available. That’s double the amount from five years earlier.

And almost 7% of Alabama teachers were in classrooms outside of their certification fields, with the highest percentages in rural areas with high rates of poverty.

Many states have loosened requirements since the COVID-19 pandemic hit, but relying on uncertified teachers isn’t new. Nearly all states have emergency or provisional licenses that allow a person who has not met requirements for certification to teach.

Such hires only delay the inevitable as the teachers don’t tend to stay as long as others, said Shannon Holston, policy chief for the nonprofit National Council on Teacher Quality.

In a 2016 study, the U.S. Department of Education reported that 1.7% of all teachers did not have full certification. It went up to roughly 3% in schools that served many students of color or children learning English as well as schools in urban and high-poverty areas.

The use of such educators can be concentrated in certain fields and content areas. One example: Alabama’s middle schools.

Rural Bullock County, for example, had no certified math teachers last year in its middle school. Nearly 80% of students are Black, 20% are Hispanic, and seven in 10 of all students are in poverty.

Christopher Blair, the county’s former schools superintendent, long struggled to recruit teachers. Poorer counties can’t compete with higher salaries in neighboring districts.

Blair, who resigned from his post last spring, had launched a program to help certify the county’s math and science teachers.

“But that’s slowly changing as the teacher pool for all content areas diminishes,” he said.

Birmingham and Montgomery each had three middle schools where more than 20% of teachers had emergency certification.

Birmingham schools spokesperson Sherrel Stewart said officials seek good candidates for emergency certifications and then give them the support needed through robust mentoring.

“We have to think outside of the box,” she said. “Because realistically, you know, that pool of candidates in education schools has drastically reduced but the demand for high-quality educators is still there.”

The number of teachers holding emergency certificates has increased dramatically in rural, urban, and low-income schools across Alabama since 2019, when lawmakers eased restrictions on the certificates.

The highest percentage of such teachers in Alabama during the 2020-21 school year was in rural Lowndes County in an elementary school where seven of 16 teachers had an emergency certificate, up from three the previous year. Most of the school’s 200 students are from low-income families. Only 1% of students tested reached proficiency in math that year.

For Dallas schools, “it’s about the passion, not about the paper,” said Robert Abel, the district’s human capital management chief.

Dallas’ uncertified hires — who must have a college degree — participate in training on classroom management and effective teaching practices. Abel said the district is getting positive reports on the new teachers.

Some teacher groups worry about inconsistent expectations for teacher candidates.

A great teacher needs sensitivity and empathy to understand how a child is motivated and what could interfere with learning, said Lee Vartanian, a dean at Athens State University. A certification helps set professional standards to ensure teachers have content expertise as well as the ability to engage students, said Vartanian, who oversees the Alabama university’s College of Education.

Uncertified teachers may have some of that knowledge, he said, but not the full range.

“They’re just less prepared systematically,” he said, “and so chances are they’re not going to have the background and understanding where kids are developmentally and emotionally.”