When Scarlett Johansson found out her voice and face had been used to promote an artificial intelligence app online without her consent, the actor took legal action against the app maker, Lisa AI.

The video has since been taken down. But many such “deepfakes” can float around the Internet for weeks, such as a recent one featuring MrBeast, in which an unauthorized likeness of the social media personality can be seen hawking $2 iPhones.

Artificial intelligence has gotten so good at mimicking people’s physical looks and voices that it can be hard to tell if they’re real or fake. Roughly half of the respondents in two newly-released AI surveys — from Northeastern University and Voicebot.ai and Pindrop — said they couldn’t distinguish between synthetic and human-generated content.

This has become a particular problem for celebrities, for whom trying to stay ahead of the AI bots has become a game of whack-a-mole.

Now, new tools could make it easier for the public to detect these deepfakes — and more difficult for AI systems to create them.

“Generative AI has become such an enabling technology that we think will change the world,” said Ning Zhang, assistant professor of computer science and engineering at Washington University in St. Louis. “However when it’s being misused, there has to be a way to build up a layer of defense.”

Scrambling signals

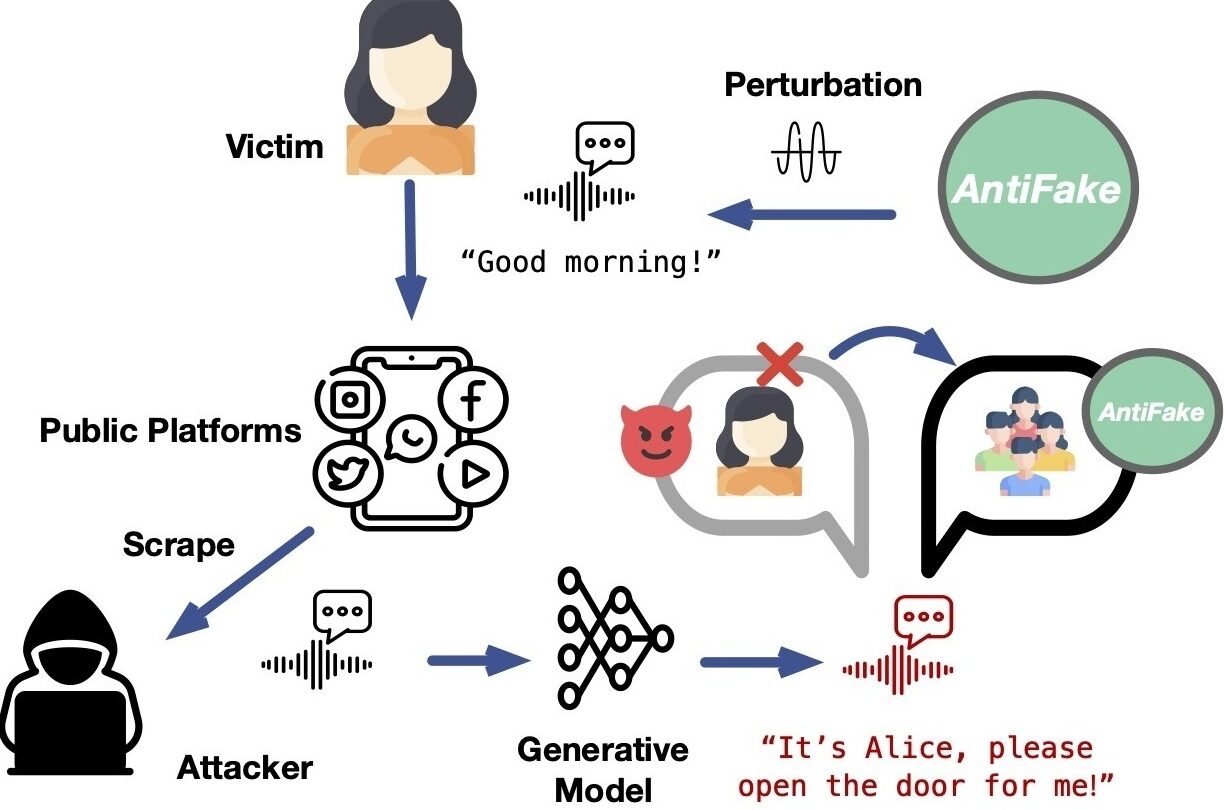

Zhang’s research team is developing a new tool that may help people combat deepfake abuses, called AntiFake.

“It scrambles the signal such that it prevents the AI-based synthesize engine from generating an effective copycat,” Zhang said.

Zhang said AntiFake was inspired by the University of Chicago’s Glaze — a similar tool aimed at protecting visual artists from having their works scraped for generative AI models.

This research is still very new; the team is presenting the project later this month at a major security conference in Denmark. It’s not currently clear how it will scale.

But in essence, before publishing a video online, you would upload your voice track to the AntiFake platform, which can be used as a standalone app or accessed via the web.

AntiFake scrambles the audio signal so that it confuses the AI model. The modified track still sounds normal to the human ear, but it sounds messed up to the system, making it hard for it to create a clean-sounding voice clone.

A website describing how the tool works includes many examples of real voices being transformed by the technology, from sounding like this:

To this:

You would retain all your rights to the track; AntiFake won’t use it for other purposes. But Zhang said AntiFake won’t protect you if you’re someone whose voice is already widely available online. That’s because AI bots already have access to the voices of all sorts of people, from actors to public media journalists. It only takes a few seconds-worth of an individual’s speech to make a high-quality clone.

“All defenses have limitations, right?” Zhang said.

But Zhang said when AntiFake becomes available in a few weeks, it will offer people a proactive way to protect their speech.

Deepfake detection

In the meantime, there are other solutions, like deepfake detection.

Some deepfake detection technologies embed digital watermarks in video and audio so that users can identify if they are made by AI. Examples include Google’s SynthID and Meta’s Stable Signature. Others, developed by companies like Pindrop and Veridas, can tell if something is fake by examining tiny details, like how the sounds of words sync up with a speaker’s mouth.

“There are certain things that humans say that are very hard for machines to represent,” said Pindrop founder and CEO Vijay Balasubramaniyan.

But Siwei Lyu, a University of Buffalo computer science professor who studies AI system security, said the problem with deepfake detection is that it only works on content that’s already been published. Sometimes unauthorized videos can exist online for days before being flagged as AI-generated deepfakes.

“Even if the gap between this thing showing up on social media and being determined to be AI-generated is only a couple of minutes, it can cause damage,” Lyu said.

Need for balance

“I think it’s just the next evolution of how we protect this technology from being misused or abused,” said Rupal Patel, a professor of applied artificial intelligence at Northeastern University and a vice president at the AI company Veritone. “I just hope that in that protection, we don’t end up throwing the baby out with the bathwater.”

Patel believes it’s important to remember that generative AI can do amazing things, including helping people who’ve lost their voices speak again. For example, the actor Val Kilmer has relied on a synthetic voice since losing his real one to throat cancer.

Patel said developers need large sets of high-quality recordings to produce these results, and they won’t have those if their use is completely restricted.

“I think it’s a balance,” Patel said.

Consent is key

When it comes to preventing deepfake abuses, consent is key.

In October, members of the U.S. senate announced they were discussing a new bipartisan bill — the “Nurture Originals, Foster Art, and Keep Entertainment Safe Act of 2023” or the “NO FAKES Act of 2023” for short — that would hold the creators of deepfakes liable if they use people’s likenesses without authorization.

“The bill would provide a uniform federal law where currently the right of publicity varies from state to state,” said Yael Weitz, an attorney with the New York art law firm Kaye Spiegler.

Right now, only half of the U.S states have “right of publicity” laws, which give an individual the exclusive right to license the use of their identity for commercial promotion. And they all offer differing degrees of protection. But a federal law may be years away.

This story was edited by Jennifer Vanasco. The audio was produced by Isabella Gomez Sarmiento.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))