All the buzz: 13-year cicadas set to emerge in Georgia

Georgia’s summer is going to sound a bit different — in fact, the last time it sounded like this was in 2011.

This year, a less-commonly seen type of cicada, the periodical cicada, will emerge for the first time in 13 years.

The Great Southern Brood is comprised of millions of cicadas that will emerge during the summer in 12 states across the southeast including Georgia. While southerners are used to hearing cicadas every year, these cicadas look and sound different. They have yellow wings and red eyes and sing different songs.

A unique life cycle

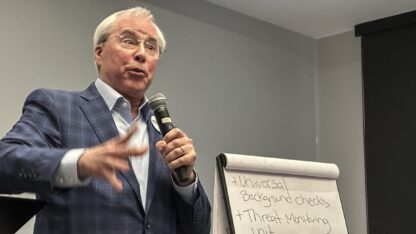

Nancy Hinkle is an entomologist at the University of Georgia. She usually studies blood-sucking arthopods, like ticks, but said cicadas are a hobby for her.

“Periodical cicadas are black with red eyes, bright red eyes, and they have orange transparent wings,” Hinkle said. In comparison, “The annual cicadas that we have every year are actually larger than periodical cicadas, they can be a couple of inches or more, and they are green with black eyes.”

Moreoever, Hinkle said you can tell the difference based on when you are seeing or hearing them. Any cicada you hear before June, Hinkle said, is going to be a periodical cicada.

The cicadas are going to come and go pretty quickly this summer.

“These cicadas have been living as immature as babies underground for 12 years and 11 months, almost 13 years, but they’re gonna come out, change into adults, mate, and start the next generation, all before June,” Hinkle said.

The next time Georgians will see them again will be in 2037. She noted there are also 17-year periodical cicadas as well.

However, Hinkle said scientists haven’t quite figured out why and how the cicadas crop up in these time intervals. There are theories, though. While the cicadas are underground, they aren’t crawling around. They are latched onto tree roots and that’s where they are getting nutrients from while they grow. Scientists think that as the trees’ sap flow changes with the seasons, the cicadas are able to “count” and emerge at the right year. Another factor they’ve looked at is soil temperature: the ground has to get up to 64 degrees Fahrenheit before the cicadas start emerging.

When they do emerge, it’s by the millions. Hinkle said that cicadas aren’t like locusts, so they won’t be swarming, but there may be noticeably more of them this summer. While some humans might not delight in the increase of big insects over the summer, it’s a boon for the animal kingdom.

“All these nutrients have been underground for 13 years, and the cicadas now are bringing them above the ground, and apparently everything out there eats cicadas!” Hinkle said.

More food means more reproduction success, so Hinkle said next year there will be a larger wildlife population.

Moreover, cicadas are pretty lousy flyers, so they tend to fall and be scattered all around, including in ponds and streams. Even fish get in on the bounty of dead cicadas.

Emerging in Georgia

Hinkle said that during the last Great Southern Brood emergence in 2011, UGA estimated that about half of Georgia counties had at least some population of the periodical cicadas. They’re most concentrated in northwest Georgia. Given the pavement and development in Atlanta, Hinkle said urbanites are unlikely to see the periodical cicadas within the metro area.

They’re set to peak around an early summer holiday.

“In fact, we recommend that everyone make plans to take your mother out for Mother’s Day to the north Georgia mountains to listen to the cicadas and watch the cicadas because that’s going to be the peak here in Georgia,” Hinkle said.

But, she said if you are on the hunt to see the periodical cicadas this summer, there are some good rules of thumb to follow.

Hinkle said periodical cicadas prefer older, undisturbed areas with trees — old growth forests, even cemeteries. They also have a preference for deciduous trees, those that lose their leaves each fall, so folks looking to find the big insects shouldn’t look in pine stands or around evergreen trees.